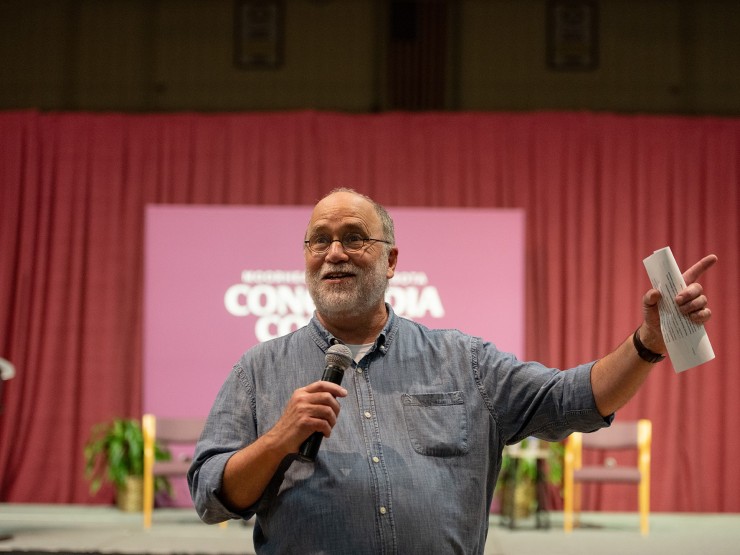

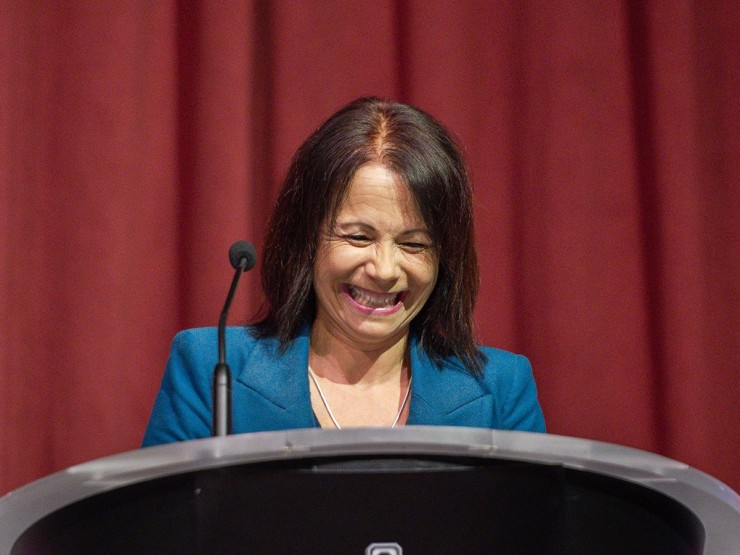

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but what do those words say, how are they used, and what’s the best way to use the visual documentation and storytelling at the core of global communication and culture? From left: President Colin Irvine moderates a panel discussion with symposium speakers Lauren Walsh, Ami Vitale, and Whitney Latorre.

From left: President Colin Irvine moderates a panel discussion with symposium speakers Lauren Walsh, Ami Vitale, and Whitney Latorre.

These were the focal points of Concordia College’s 2023 Faith, Reason, and World Affairs Symposium, “Creating the Visual Record,” Sept. 19-20, which brought together experts in photojournalism, technology, and an array of academic disciplines for a wide-ranging discussion.

Issues under the magnifying glass included ethics, community standards, new technologies such as artificial intelligence, accuracy, bias, entertainment vs. shock value, and appropriate use of images in various contexts.

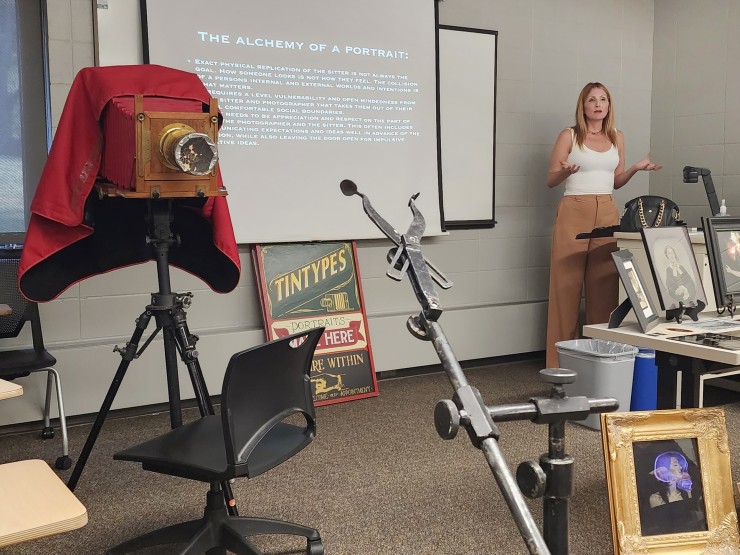

Attendees had the opportunity to listen to presentations from nationally known photojournalists and a roundtable conversation between the keynote speakers and President Colin Irvine. They could also choose two of 14 presentations from regional photographers, Forum Communications journalists, and college faculty and staff on topics ranging from historical and sports photography to fake photos and images produced by AI. (more photos from concurrent sessions in gallery below)

Visual Storytelling and National Geographic

Whitney Latorre, former director of visuals and immersive experiences at National Geographic, kicked off the symposium with a call to photographers to expand and seize the moment.

“I think we should move visual storytelling as far forward as technology and truth can go,” Latorre said. “What we’re after, after all, is impact.”

During her presentation, Latorre showcased the history of National Geographic Magazine, including its first printed photo of a natural scene, its pioneering efforts in color underwater and aerial photos, and its use of technological innovation to strengthen visual storytelling.

Though sometimes criticized as a “picture book,” the National Geographic was using a new form of storytelling and, over time, that storytelling began to make a difference. Images of Yosemite National Park showed the West to the world and led to the Yosemite Act, which protected the region. Photos of animals, such as elephants in Gabon, led to conservation efforts.

“Publishing a photo is just the beginning of a conversation,” Latorre said.

That conversation is changing as generative AI and augmented reality become more prevalent, but technology can’t replace an artistic eye, said the National Geographic alumna.

Latorre has been telling stories as long as she can remember and, in college, majored in English.

“Students, don’t limit yourselves or let anyone box you in,” she advised, noting that the core values of storytelling don’t change whether the medium is text-based or photographic and still require meaningful content and strategic delivery. One medium does not need to replace another, Latorre added.

Caring and Conflict Photography

Photojournalist, writer, and educator Lauren Walsh, who specializes in conflict photography and peace journalism, was once taken aback in the classroom as she was showing students photos of people suffering during a famine in Sudan.

One of her students said that while he understood why she was presenting the information, he had plans to go to dinner later, that he “had nothing to do with the suffering,” and asked why he should care.

Walsh turned the question back to her other students, who weren’t pleased with the commenter, but the question lingered with her. She mentioned it to a photographer friend, who said they’d heard those questions for a long time.

Walsh began working on “Conversations on Conflict Photography” to address the specialization’s goals and effects and interrogate its purpose and often complex ethical dilemmas in a world of apathy and news exhaustion.

She described some of the risks of conflict photography and journalism, starting with the physical danger, but also including the incredible emotional toll it can take on the photographers who must see disturbing images to capture them.

“There is a person there who is creating the imagery,” Walsh said.

She described the balancing act between creating a beautiful image that draws attention and encourages people to care, and accurately portraying human suffering and horror. Walsh also pointed out the mythic romanticism of conflict photojournalism, which has largely been a Western, white male’s job, and emphasized the importance of including many voices.

“It’s not just making a photo. It’s not just taking a photo. There’s so much thinking that needs to go into it,” Walsh said of photojournalism.

She noted that journalism is expensive and is currently undergoing a financial crisis as people gravitate toward social media and away from paid subscriptions. In the long term, Walsh warned, that erodes the ability of media organizations to produce strong, in-depth work.

War and Conservation

Ami Vitale, National Geographic photographer and filmmaker, told attendees that she had once been a shy, awkward kid. With a camera, she could forget about herself and focus on others, amplifying their stories and their voices.

“In the beginning, it was the tool for my own self-empowerment,” Vitale said. “But I quickly realized the more extraordinary thing is that you can create awareness and understanding and connect people.”

At a young age, she received a grant and traveled to a small village in West Africa where a civil war had impacted the people. By slowing down and allowing people to tell her what their stories were, she learned that there were many characters and that the story she wanted to tell was their deep connection to the natural world.

At another point, while she served as a conflict journalist, Vitale was told to get dramatic pictures of the war, but she began asking herself whether the reporters there were telling only half the story. On her way back to her hotel one day, she discovered a couple getting married in the middle of the chaos — a true example of human resilience.

She started focusing more on the human condition, the natural world, and how resources often drive conflict in humans.

Vitale has taken photos of the people fiercely protecting endangered rhinoceros populations from poachers, people consoling baby elephants separated from their herds, and people taking drastic measures to reintroduce pandas back into the wild.

Vitale emphasized the importance of doing research but also cautioned attendees against assuming they know someone else’s story. She encouraged people to push the envelope, telling stories of hope and resilience.

“We need to come together and find ways to tell the stories,” she said.

Main session photos by Penny Burns